Copper is pathological and suffers from SAD, but it has value - Goldie

Dr. Copper may be in a supercycle, but there are serious problems. Raymond Goldie explains that the base metal acts pathologically and has a bad case of seasonal affective disorder. Gold Report interview.

Author: JT Long

Posted: Thursday , 17 Apr 2014

TORONTO -

The Gold Report: You are giving a presentation at the Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration Current Trends in Mining Finance Conference called Diagnosing the Doctor, which refers to assessing the supply and demand problems for Dr. Copper as a way to understand what is ailing all the mining products today. Are we in a supercycle? What is the meaning of a sustainable supercycle?

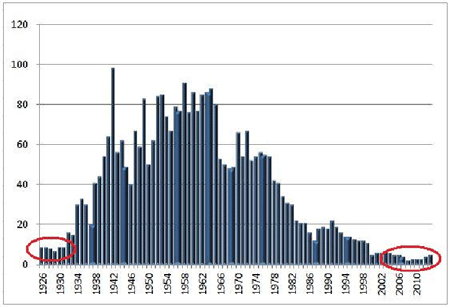

Raymond Goldie: I suppose it's best to answer your second question first—What is the meaning of a sustainable supercycle?—because a lot of people use the word supercycle to describe the wonderful state that we had beginning in the early part of this century, when metal prices kept going up, commodity prices kept going up, seemingly forever. I'm a little less restrictive on what I define as a supercycle. I think a supercycle is any period in which we have commodity prices higher than their long-term average values. On that basis, even allowing for overall inflation, we've been in a supercycle since 2004. We're still in it, although for a few months regrettably at the end of 2008 we popped out of it. But right now we are in a supercycle.

TGR: What are the fundamentals keeping us in your definition of a supercycle?

RG: The usual reason is China. It's the biggest consumer of most of the commodities in the world and has the biggest growth in consumption of most of the commodities in the world. But what that analysis tends to overlook is that production of most commodities in China has been increasing at roughly the same rate as consumption in China. So, on balance, China may not be as big a contributor to the supercycle as we've imagined.

TGR: Does that mean that the Western world is playing a larger role in supporting the supercycle than we give it credit for?

RG: When it comes to assessing supply and demand from Asia, it is important to consider Chinese economic data, which a recent Bloomberg article equates to some of the meat served in low-cost restaurants. We don't know where it comes from and don't really know what it means. It's not easy to put a lot of credence on Chinese economic numbers, so it's hard to tell the extent to which China does affect supply and demand.

But one thing that we can count on is the diligence of people who sit at borders with clipboards looking at stuff crossing borders. They are paid to make sure that the right duties get paid and the ships are carrying what they're supposed to be carrying. If we look at China's trade with the rest of the world, those numbers are fairly reliable, even if the numbers for what's going on inside China are not reliable. Since 2008, the dark days when the world seemed to have ended, China's imports of copper from the rest of the world have grown 41% per annum.

TGR: And what about the supply side?

RG: I think the single most important reason that we're in a sustainable supercycle is that we haven't invested enough in finding more resources. The supply-side constraints are probably why prices are higher than the long-term trend in prices.

TGR: Why has it been so difficult to predict how much copper will be produced in a given year if it takes so long to bring a mine to production?

RG: Since about 2003 analysts have consistently overestimated the production of copper. My theory for the consistent shortfall is that before 2003, when strikes, landslides, earthquakes, storms, civil unrest, late trains and the like slowed down production, someone in the head office would send a cable calling for the mining of high-grade ore to make up the difference. But since 2003, there hasn't been any high-grade ore to mine because of a lack of investment in new resources. And this happens year after year. About 7% less copper is produced each year than the mines predicted at the start of the year.

TGR: So why isn't that inconsistency causing the price to go up?

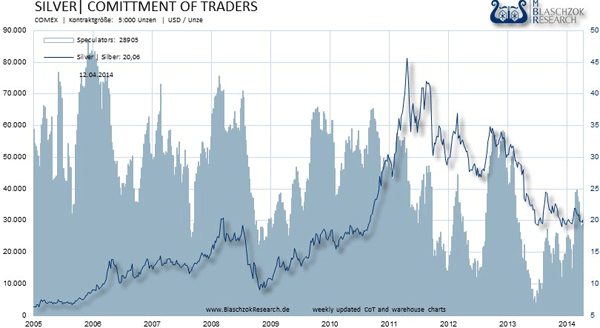

RG: Maybe it is. There has certainly been what I've called a pathological situation in the copper markets because typically the relationship between copper inventories—the stuff that's sitting around in warehouses—and prices is that the lower the inventories, the higher the price. But since 2005, in the Western world—we don't know what's going on in China—inventories have gone up 185%. Typically, that would mean prices go down, right? But, no, prices have gone up 95%. That may be one of the reasons that we're consistently producing less of the stuff than we thought we could.

TGR: You have said that the pitch-point™ curve* for supply and demand compared to prices is pathological. Is that because of the role of recycling in meeting some of the demand?

RG: I think it could be because it used to be that every pound that was in inventory was backed by all the copper that the mines would produce and all the copper that scrap yards would produce. The amount that the scrap yards produce has been declining, in large part because Asians have been very diligent about taking scrap from North America and refining it into good usable copper again. But, again, it's hard to get good figures for how much copper there is in scrap yards so that answer is probably yes, the declining use of copper in recycling is probably one of the reasons why we've seen prices go up even though inventories have also gone up. But it's hard to be more precise than that.

TGR: You have also said that copper has seasonal affective disorder (SAD). What causes that?

RG: That's right, it does. I can tell you what SAD is, but I can't tell you exactly what causes it. In the good old days of the London Metal Exchange (LME), the saying was "sell in May and go away." And that was always a wonderful excuse to take an English summer holiday and not bother coming back to trade copper until September or October. Now, the peak seems to be around the end of February and the end of June tends to be the bottom in copper prices. It's pretty consistent. Year after year we see that effect, but what causes it, I don't know.

TGR: Because copper is so important for growth, is it feasible that it could be used as the world reserve currency instead of gold or the dollar? What would that look like?

RG: Copper is being used as a reserve currency in China right now. Some of the importers will use the copper that they hold as collateral for loans that they make from various banks in China. One of the advantages of copper as collateral is that unlike wheat, silver or potash, you can store it outside. Even in the rain, copper will keep its value, and there's always a use for the stuff.

But to talk about copper as a reserve currency for the whole world is not practical. If a country is holding reserves of $1 trillion, it would have to have 150 million tons on reserve. That is about eight and a half years of copper consumption just sitting there. But certainly copper is being used as a currency on a small scale, as it's being used now in China.

TGR: What prices are you using for copper going forward in the rest of 2014?

RG: Since 2003 when the fundamentals of the copper business changed so significantly, the forward prices on the LME have been a much better forecaster of copper prices than we analysts. This afternoon, the LME is telling me that if I buy copper now for delivery in 10 years, I would have to pay $3.02/pound ($3.02/lb). That's as good as any forecast I have for the long-term price of copper. If you were to buy a pound of copper for delivery tomorrow, it's pretty much the same as where the price of copper is today.

TGR: If copper prices look to be fairly flat going forward, why do copper equities tend to outperform the metal?

RG: This gets back to the unwieldy nature of copper as a store of value. Let's say you were thinking of retiring and decided to make off with all of your fortune, say $3 million ($3M), and drive away into the sunset. Now, if you put that in the form of gold, $3M would weigh less than 200 lb; it would fit in the trunk of your car. But $3M worth of copper would weigh 450 tons. That is why when people get enthusiastic about buying gold, they often buy gold bullion. But when they're thinking of buying copper, the unwieldy nature of buying copper metal means they are better off with the equities. That's why the equities have done about the same or even a little better than the price of copper itself. That certainly has not been the case with gold.

TGR: Are the copper companies less risky than some of the gold companies?

RG: Riskiness is a feature of the things that Mother Nature can fling at us or the surprises that come with the election of a government that no one expected and that government nationalizes some of its assets. Most of the companies that I follow are managed by a lot of gray hairs; they've seen all the unpleasant things that can happen. Most of the ones that I tend to look at are well managed, and they include the big producers

TGR: Do you evaluate a company in the tailing business very differently than a company with a different business strategy?

RG: I don't actually. I generally use the standard textbook discounted cash flow valuation method. For a mine in production, I use a low discount rate. For potential expansion, I use a higher discount rate because this is an unproven technology there. I use an even higher discount rate on something that isn't in production yet, simply because of the technological, political and community risks associated with that prospect.

TGR: With all of these great ideas, what advice do you have for resource investors who are looking to keep their portfolios healthy during the next two or three years while they wait for some of these things to happen?

RG: There are two questions that investors should ask about any investment they make: Is the value there? When should I seize on that value? Most copper mining stocks are trading as if the price of copper were $2/lb and is going to be about $2/lb forever. But copper on the LME 10 years out is actually $3/lb. That means the equities are definitely a value story. As to when to buy it, given the SAD cycle we mentioned earlier, investors might want to wait until the end of June.

TGR: Thank you for your advice.

RG: Thank you.

Dr. Copper may be in a supercycle, but there are serious problems. Raymond Goldie explains that the base metal acts pathologically and has a bad case of seasonal affective disorder. Gold Report interview.

Author: JT Long

Posted: Thursday , 17 Apr 2014

TORONTO -

The Gold Report: You are giving a presentation at the Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration Current Trends in Mining Finance Conference called Diagnosing the Doctor, which refers to assessing the supply and demand problems for Dr. Copper as a way to understand what is ailing all the mining products today. Are we in a supercycle? What is the meaning of a sustainable supercycle?

Raymond Goldie: I suppose it's best to answer your second question first—What is the meaning of a sustainable supercycle?—because a lot of people use the word supercycle to describe the wonderful state that we had beginning in the early part of this century, when metal prices kept going up, commodity prices kept going up, seemingly forever. I'm a little less restrictive on what I define as a supercycle. I think a supercycle is any period in which we have commodity prices higher than their long-term average values. On that basis, even allowing for overall inflation, we've been in a supercycle since 2004. We're still in it, although for a few months regrettably at the end of 2008 we popped out of it. But right now we are in a supercycle.

TGR: What are the fundamentals keeping us in your definition of a supercycle?

RG: The usual reason is China. It's the biggest consumer of most of the commodities in the world and has the biggest growth in consumption of most of the commodities in the world. But what that analysis tends to overlook is that production of most commodities in China has been increasing at roughly the same rate as consumption in China. So, on balance, China may not be as big a contributor to the supercycle as we've imagined.

TGR: Does that mean that the Western world is playing a larger role in supporting the supercycle than we give it credit for?

RG: When it comes to assessing supply and demand from Asia, it is important to consider Chinese economic data, which a recent Bloomberg article equates to some of the meat served in low-cost restaurants. We don't know where it comes from and don't really know what it means. It's not easy to put a lot of credence on Chinese economic numbers, so it's hard to tell the extent to which China does affect supply and demand.

But one thing that we can count on is the diligence of people who sit at borders with clipboards looking at stuff crossing borders. They are paid to make sure that the right duties get paid and the ships are carrying what they're supposed to be carrying. If we look at China's trade with the rest of the world, those numbers are fairly reliable, even if the numbers for what's going on inside China are not reliable. Since 2008, the dark days when the world seemed to have ended, China's imports of copper from the rest of the world have grown 41% per annum.

TGR: And what about the supply side?

RG: I think the single most important reason that we're in a sustainable supercycle is that we haven't invested enough in finding more resources. The supply-side constraints are probably why prices are higher than the long-term trend in prices.

TGR: Why has it been so difficult to predict how much copper will be produced in a given year if it takes so long to bring a mine to production?

RG: Since about 2003 analysts have consistently overestimated the production of copper. My theory for the consistent shortfall is that before 2003, when strikes, landslides, earthquakes, storms, civil unrest, late trains and the like slowed down production, someone in the head office would send a cable calling for the mining of high-grade ore to make up the difference. But since 2003, there hasn't been any high-grade ore to mine because of a lack of investment in new resources. And this happens year after year. About 7% less copper is produced each year than the mines predicted at the start of the year.

TGR: So why isn't that inconsistency causing the price to go up?

RG: Maybe it is. There has certainly been what I've called a pathological situation in the copper markets because typically the relationship between copper inventories—the stuff that's sitting around in warehouses—and prices is that the lower the inventories, the higher the price. But since 2005, in the Western world—we don't know what's going on in China—inventories have gone up 185%. Typically, that would mean prices go down, right? But, no, prices have gone up 95%. That may be one of the reasons that we're consistently producing less of the stuff than we thought we could.

TGR: You have said that the pitch-point™ curve* for supply and demand compared to prices is pathological. Is that because of the role of recycling in meeting some of the demand?

RG: I think it could be because it used to be that every pound that was in inventory was backed by all the copper that the mines would produce and all the copper that scrap yards would produce. The amount that the scrap yards produce has been declining, in large part because Asians have been very diligent about taking scrap from North America and refining it into good usable copper again. But, again, it's hard to get good figures for how much copper there is in scrap yards so that answer is probably yes, the declining use of copper in recycling is probably one of the reasons why we've seen prices go up even though inventories have also gone up. But it's hard to be more precise than that.

TGR: You have also said that copper has seasonal affective disorder (SAD). What causes that?

RG: That's right, it does. I can tell you what SAD is, but I can't tell you exactly what causes it. In the good old days of the London Metal Exchange (LME), the saying was "sell in May and go away." And that was always a wonderful excuse to take an English summer holiday and not bother coming back to trade copper until September or October. Now, the peak seems to be around the end of February and the end of June tends to be the bottom in copper prices. It's pretty consistent. Year after year we see that effect, but what causes it, I don't know.

TGR: Because copper is so important for growth, is it feasible that it could be used as the world reserve currency instead of gold or the dollar? What would that look like?

RG: Copper is being used as a reserve currency in China right now. Some of the importers will use the copper that they hold as collateral for loans that they make from various banks in China. One of the advantages of copper as collateral is that unlike wheat, silver or potash, you can store it outside. Even in the rain, copper will keep its value, and there's always a use for the stuff.

But to talk about copper as a reserve currency for the whole world is not practical. If a country is holding reserves of $1 trillion, it would have to have 150 million tons on reserve. That is about eight and a half years of copper consumption just sitting there. But certainly copper is being used as a currency on a small scale, as it's being used now in China.

TGR: What prices are you using for copper going forward in the rest of 2014?

RG: Since 2003 when the fundamentals of the copper business changed so significantly, the forward prices on the LME have been a much better forecaster of copper prices than we analysts. This afternoon, the LME is telling me that if I buy copper now for delivery in 10 years, I would have to pay $3.02/pound ($3.02/lb). That's as good as any forecast I have for the long-term price of copper. If you were to buy a pound of copper for delivery tomorrow, it's pretty much the same as where the price of copper is today.

TGR: If copper prices look to be fairly flat going forward, why do copper equities tend to outperform the metal?

RG: This gets back to the unwieldy nature of copper as a store of value. Let's say you were thinking of retiring and decided to make off with all of your fortune, say $3 million ($3M), and drive away into the sunset. Now, if you put that in the form of gold, $3M would weigh less than 200 lb; it would fit in the trunk of your car. But $3M worth of copper would weigh 450 tons. That is why when people get enthusiastic about buying gold, they often buy gold bullion. But when they're thinking of buying copper, the unwieldy nature of buying copper metal means they are better off with the equities. That's why the equities have done about the same or even a little better than the price of copper itself. That certainly has not been the case with gold.

TGR: Are the copper companies less risky than some of the gold companies?

RG: Riskiness is a feature of the things that Mother Nature can fling at us or the surprises that come with the election of a government that no one expected and that government nationalizes some of its assets. Most of the companies that I follow are managed by a lot of gray hairs; they've seen all the unpleasant things that can happen. Most of the ones that I tend to look at are well managed, and they include the big producers

TGR: Do you evaluate a company in the tailing business very differently than a company with a different business strategy?

RG: I don't actually. I generally use the standard textbook discounted cash flow valuation method. For a mine in production, I use a low discount rate. For potential expansion, I use a higher discount rate because this is an unproven technology there. I use an even higher discount rate on something that isn't in production yet, simply because of the technological, political and community risks associated with that prospect.

TGR: With all of these great ideas, what advice do you have for resource investors who are looking to keep their portfolios healthy during the next two or three years while they wait for some of these things to happen?

RG: There are two questions that investors should ask about any investment they make: Is the value there? When should I seize on that value? Most copper mining stocks are trading as if the price of copper were $2/lb and is going to be about $2/lb forever. But copper on the LME 10 years out is actually $3/lb. That means the equities are definitely a value story. As to when to buy it, given the SAD cycle we mentioned earlier, investors might want to wait until the end of June.

TGR: Thank you for your advice.

RG: Thank you.